Rendering textile stories in aluminum and LED: An interview with CreateSpace artist Roda Medhat

Clean-cut and spray-painted in vivid red, Roda Medhat’s FARSH 2 translates the traditional handcraft of the Kurdish rug into the industrial medium of aluminum signage. FARSH 2, created for the STEPS CreateSpace Public Art Residency, is part of the artist’s long-running exploration of the Kurdish rug in novel and arresting mediums, such as the lighting sculptures LED FARSH and Marital Rug.

In his artistic practice, traditional emblems of Kurdish identity and craftsmanship are brought into dialogue with industrialized processes of manufacturing. From the practical houseware of a rug to the commercial advertisement of an LED sign, Roda Medhat’s work reminds us of the histories of manufacture and private use behind every aesthetic object. In an interview with Wenying Wu (STEPS Cultural Content Writer) at his studio in Toronto arts hub 401 Richmond, the artist explains the translation of tradition into industrial and commercial mediums, as well as the value of starting conversations about Kurdish culture in public spaces.

From left to right: Negative cut-out of FARSH 2, LED FARSH, Aluminum Rug, and Wall Rug Missing Tacks by Roda Medhat

Photo credit: Ayesha Khan (Stories at the Table)

This feature is part of Fieldnotes, a public art blog series by STEPS that promotes inclusive and innovative public art through interviews, storytelling, case studies, and knowledge sharing.

Artist Interview with Roda Medhat

Wenying Wu (WW): At STEPS we know you through FARSH 2, a project with the CreateSpace Public Art Residency. Would you like to share a bit about the piece?

Roda Medhat (RM): The negative cut-out of the project I did with STEPS is right here in the studio. In a lot of my work, I’m exploring Kurdish textiles, but in different mediums. In work that I did prior, I was using actual textiles. But then for STEPS, I was thinking: what medium can I use that has a little bit more longevity? So I was like, I can work with steel and aluminum, and I was looking at laser cutting. The fabrication was a process just thinking about what materials I can use, what mediums work well.

The difference with working with textiles versus something two-dimensional like steel, you can’t work with as much colour and shapes. The reason these rugs are so vibrant and work so well is because they use colour and shape and overlap to pull all these different symbols and designs together. So there was a challenge there to simplify the work enough that it works in this medium. And now it’s installed in a community center in Mississauga until May of 2025.

FARSH 2 installed at Erin Meadows Community Centre in Mississauga

Photo credit: Sofia Habib

WW: There’s a sleek minimalism in the design which seems to play with themes of modernization: the blend between modernity and traditionalism and these industrial cycles of production caught up in all of our traditional practices.

RM: When I was exploring this work in particular, I was also having conversations with people about traditional clothes, traditional textiles and stuff back in Kurdistan where I’m from. And these used to be handcraft that people would produce locally. You had local tailors creating things, local artisans. But then a lot of that production was moved east to China where it could be mass manufactured in factories. And it was funny to us locally to think that someone in China was creating Kurdish clothes. Are they just producing something that someone sent to them or did they start creating it on their own knowing that there was a demand? And it’s this very distinct thing. It’s not just generic clothes, which could be produced anywhere. It’s a very distinct cultural item that holds significance in the culture. So it was funny to have that connection that these things are being mass produced.

Even textiles are mass produced. These rugs that I have here are made on a machine. They’re not hand woven or anything. So I was thinking about that—machine-made versus handmade. This was all designed on a computer and then laser cut, water jet cut with a machine. The hand has really been removed from craft. It’s all machine-driven.

That’s kind of what I was looking at with FARSH 2. Traditional handmade rugs have a lot of errors and mistakes in them that make them kind of more interesting. But then this, it’s like because it’s made out of a machine, it’s this level of perfection that you can’t achieve by hand either. There’s an interesting interplay there with a traditional handmade rug.

WW: The aesthetic is very streamlined, very clean, and that has a beauty of its own, but it’s alienated a little bit from its origins, right?

RM: Because of its perfection, it’s immediately recognizable as a rug. But as you look at it more, it’s hard to distinguish where it comes from. When you look at antique rugs, you can tell where they come from based on the handcraft, how certain stitches are done, how weaves are done, how the finishes are done. And each region has its own finishes. But when it’s done with a machine, it loses that ability to distinguish where it comes from regionally and historically.

Installation of FARSH 2

Photo credit: Sofia Habib

WW: There’s this orientalizing idea, that all rugs are the same. All eastern cultures have the same art.

RM: Exactly, yeah. When it’s machine-made, it does kind of orientalize everything.

WW: What motivates these explorations and re-explorations of the Kurdish rug motif?

RM: A lot of times I think about my culture, my identity. When I talk about being Kurdish, there’s a lot of questions. People don’t always know what that is. And even around the world, a lot of the Kurds are displaced amongst a bunch of countries, and in those countries they face a lot of discrimination and kind of denial of their existence. So I was thinking, how can I bring this conversation about Kurdish identity to the forefront? The easiest way is to create work that’s captivating and interesting and easily recognizable as a foot in the door for people to be like, oh, I like the way this looks. From there, when they read the artist description or deep dive into the work a bit more, they get introduced to Kurdish culture, Kurdish identity and the politics around that.

I wanted to create work that was easily accessible. You can dive into the work quickly just because it is captivating, especially with the light-up works. It draws you in. From there, it’s easy to be pulled into the conversation.

WW: Having completed several pieces of public art, do you feel any particular tensions or potentials when bringing Kurdish culture to public spaces?

RM: A lot of my public work is big and bold and very obviously from a different region, not local. I think there’s that exoticism that I play into, and people find that interesting, and I don’t mind creating a soft “in” for people to come into the work. It’s easily recognizable and they can exotify or whatever just to get into the work, and then from there, have a conversation to bring more depth to it other than what they immediately understand as a Persian rug or something like that.

A lot of times, my concern when I’m creating work is not local Westerners misunderstanding the work, but more people from the region, because a lot of the tensions that exist in the region of Kurdistan with locals, they also exist here. People locally in Canada that have immigrated here will deny the culture or start fights and bicker. I haven’t had any of that, but that’s often what is at the forefront of my mind more so than the Western gaze.

From left to right: Aluminum Rug, negative cut-out of FARSH 2, LED FARSH, and Wall Rug Missing Tacks

Photo credit: Ayesha Khan (Stories at the Table)

WW: And in grappling with those tensions, there’s the difficulty of the limits of expression of any piece. Like, how much nuance in your head can you show in a way that’s readable to the general audience?

RM: Yeah, I definitely try to make the Kurd aspect of it as in the forefront as I can. It’s difficult with textiles though, because the craft and the symbolism and the design are regionally shared a lot. Even when you go to the Balkans, which is west of Asia, or you go all the way to East Asia and China, you can find examples of rugs that use the same symbols. If you go to Croatia, Bosnia, up to Ukraine even, you can find rugs that share similar symbolism. So it’s hard to create something that’s distinctly of one region when it’s made of a different material. When it’s the original textile, there are things that are distinctly Kurdish or distinctly from another region.

I try as much as I can to make it distinctly Kurdish, even if it’s just in the artist description. And it’s almost a political act to put my identity on the forefront. When your identity is denied by others, it gives you an opportunity to really boldly say, I’m here and I exist.

WW: In relation to identity, a lot of your work seems to gravitate towards cultural hybridity, especially the necessary hybridity that happens with modernization and globalization, cultural exchange for all its ups and downs.

RM: I think the hybridity in my work comes from the fact that I was born in Kurdistan, but we moved here when I was a toddler. So you’re never fully immersed in one culture or another. There’s a bit of distance between me and the culture, and I can’t duplicate the work exactly because of that distance. As much research and studying I do about textiles and art of the region, there’s always some level of distance. The only way I can approach it is through hybridity. By creating a buffer, if there are mistakes or misunderstandings in my research, that buffer gives me that room to play with and create work that’s referencing without being exactly of the region or a copy of that.

WW: This cultural hybridity really seems to dovetail with a lot of your choices of medium, LED and aluminum, blending these technological, modernizing aesthetics with traditional motifs.

RM: I think with every work that I do, it’s an experiment and it’s studying and it’s education and research. With every piece that I make, I’m just like, what can we look at? How can we recreate these rugs or textiles or history in other mediums? I like to look at industrial things, research what kind of tools and materials exist out there that aren’t necessarily art-specific or medium-specific. A painter would look at other paints and pigments, but for me, I just look at what exists out there as a ready-made object, and then figure out how I can blend that into the work.

So these light up rugs, I made with a fabrication studio that does storefront signs, though they’ve never made art-based signage.There are studios that do specific neon signs for artists, but I like to work with more industrial commercial places. There’s a level of navigation and relationship building that differs from when you’re working with artists. One time I created a sculpture out of those construction convex mirrors. I just found a construction factory that made those things, and I ordered a bunch and turned it into a sculpture.

In terms of technology, I think it plays into that whole hybridity thing, just seeing what exists out there and blending that in and working with mediums that are easily recognizable and attractive and using that as kind of a pull for the audience into understanding Kurdish culture and Kurdish identity and willing to be part of the conversation.

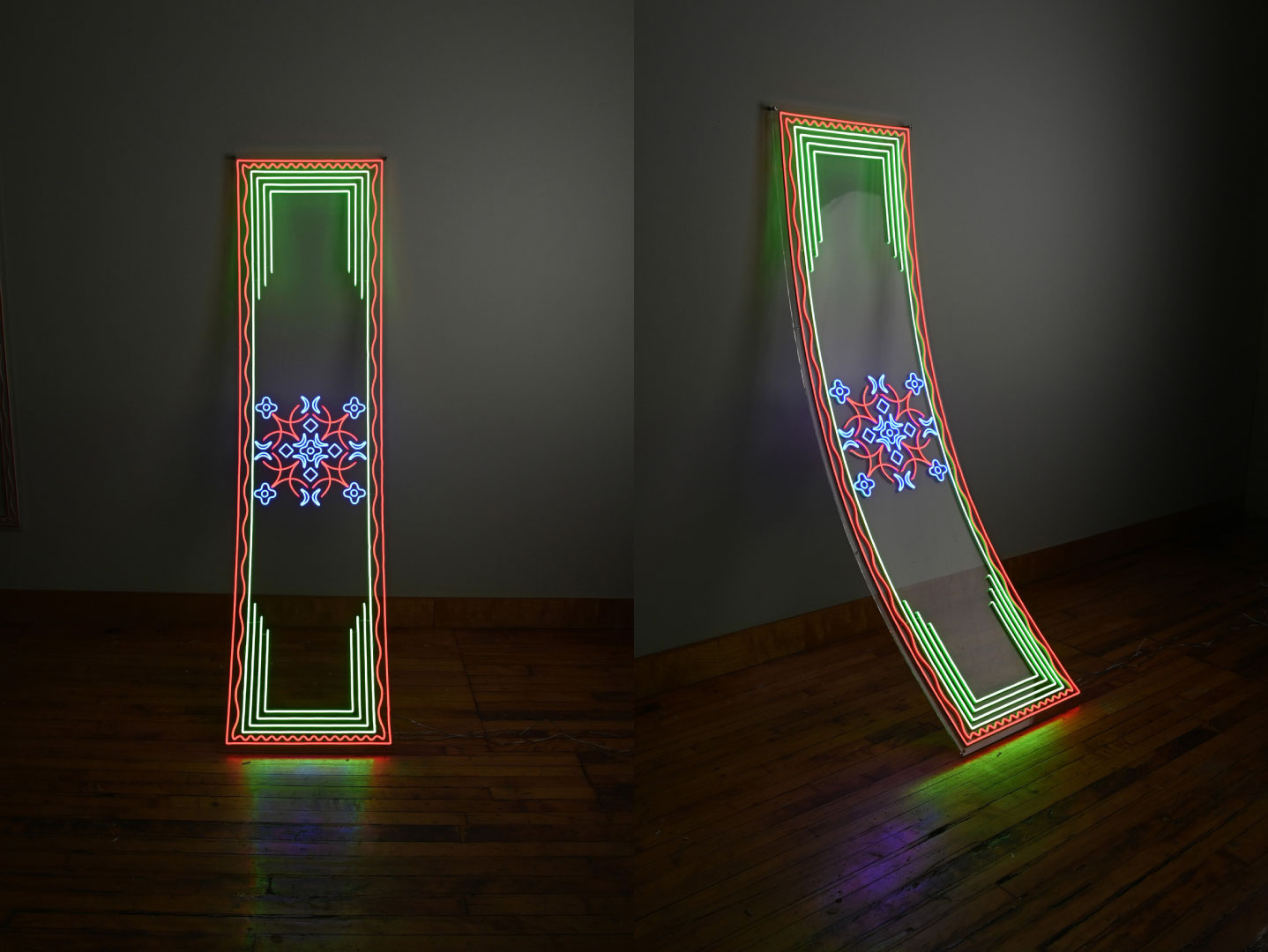

From left to right: LED FARSH, Wall Rug Missing Tacks, and Marital Rug

Photo credit: Ayesha Khan

WW: I see the affinity for crafts, in the whole arts and crafts dichotomy. Since you’re drawing from the Kurdish rug, there are resonances with non-Western artistic traditions of works that have practical uses apart from the artistic.

RM: Yeah. It’s something I think about too. Rugs are very multifaceted. They’re practical goods. People use it to sit on, to drape their homes with. If they’re nomadic families, their houses will be made of textiles and rugs. But they’re also these revered objects. You could buy handmade Persian rugs for tens, hundreds of thousands of dollars. It’s interesting how they’re handcraft and often will look similar or be made of similar materials, but have different levels of value depending on where you place them. Is it on the floor? Is it on the wall? Is it in a gallery? And who’s the one selling it, who acquired it? These little decisions decide if a craft is of value or not.

Sometimes with the work, I like to be in that in-between of a practical object versus an object of beauty just to be revered. How much more can you push the medium of textiles and how can we see textiles in another light other than just what westerners see as a Persian rug? What is it beyond that?

WW: And LED, it’s a medium that really translates that practical but revered sensibility of the rug into the modern urban cityscape, as part of these hypermodern aestheticized images of the city as this beacon of the new.

RM: A couple years ago, I took a trip to Hong Kong. Historically, everything was neon signs, but when I went, they had just removed 90% of the neon signs to be replaced by LEDs. And I was always thinking about that and how interesting that was, and switching to LED because it’s more practical and energy efficient. For Hong Kong, I think it was a shame almost because the way neon lights produce colour is different than these LEDs. It was kind of like a step back for them in terms of just aesthetic.

But when I worked with it here, I don’t know if it’s a step up from the aesthetic of textiles, I don’t think it is, but I think it just pulls people in a bit easier. And like I was saying before, I just want to draw people in first and then have that conversation second, because it’s hard to get people involved. If you’re ignorant of a subject, a lot of people are standoffish and don’t want to engage. They just feel judged and unable to have a conversation around culture and identity. So to have something that’s an easy pull and then having the conversation from there, I think breaks down a lot of barriers that people are afraid to overstep.

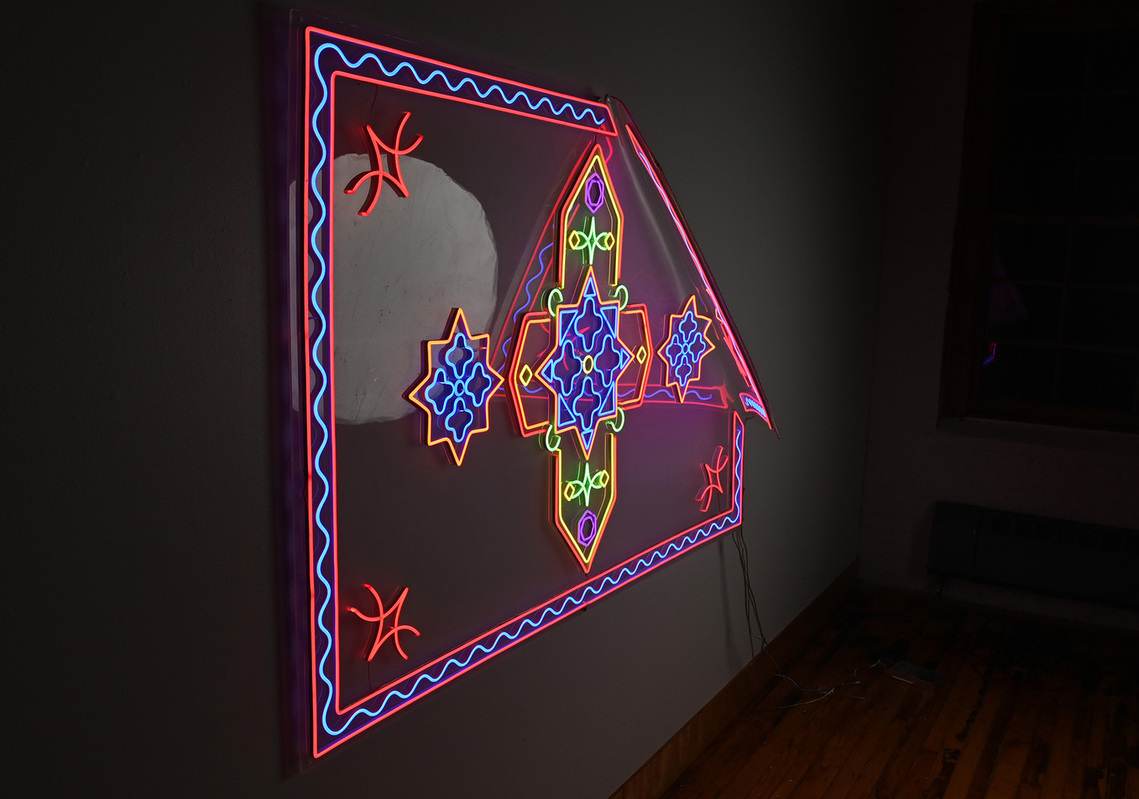

Marital Rug

Photo credit: Roda Medhat

WW: On the topic of LEDs, one of my favourites of yours is Marital Rug. I love the playful sagging curve that reminds you of a textile’s materiality, even in a medium that’s so different.

RM: First I created these two light pillars, LED FARSH. They reference the design language of rugs, but miss that sense of life. Then I was exploring: how do I bring the life back into the rugs? The thing about rugs, if you think about nomadic homes and active living spaces, things are being put up, taken down, things fall off the wall, things sag, things move over time. I wanted to put the weight back into the work.

Then came these two, Marital Rug and the rug beside it, Wall Rug Missing Tacks. With Missing Tacks, I was imagining the rug falling off the wall. The tack has fallen out and it needs to be placed back. With Marital Rug, I was thinking of the weight of rugs, these heavy textiles. I was on a trip back to Kurdistan recently, and I came back with a suitcase full of rugs, and it was like a hundred pounds. So I was imagining the weight of the rug and of the meaning of the rug. Often rug makers fill them end to end with design work, but there’s a design language where they leave large open green spaces, like empty space to contemplate God or to contemplate love or life.

I wanted to create these massive blank spaces of contemplation, and then in the center have this floral garden motif weighing it all down. There’s the ideas of contemplation and reflection, but also the practicality of a rug. It’s this heavy object that’s hung on the wall, that can fall or sag, that has life to it. Maybe someone’s in the process of putting this up. I really wanted the life behind the rug to exist.

WW: A lot of artworks or crafts will necessarily end up in depersonalized galleries spaces, but the weight represents the personal and private roles of the rug?

RM: And a lot of times these rugs held stories, and there are a lot of short stories that talk about, oh, a rug maker was making something, and someone would walk by and see it and could tell the whole person’s life through the symbols in the rug. And when you read these texts, they talk about young women who were rug makers when they were getting ready to be married or they had the intention of being married. They would weave in symbols into the rug to tell their family, I want to be married or find me a spouse. Something we think of as simple as a rug, it can say a lot that you can’t communicate verbally.

Wall Rug Missing Tacks

Photo credit: Roda Medhat

WW: Young women looking for a partner, that’s where the symbolism of Marital Rug draws from?

RM: This one references a rug about Sufism and religion and the contemplation of God. I reinterpreted the religious rug into this kind of marital rug and the weight that sometimes these stories tell. I read this short story about this woman who was being married off to a man that she didn’t want. A king was passing through the village and saw the rug, and he started crying, and the father of the woman who was selling the rug asked, “Why are you crying?” He said, “I can see that your daughter doesn’t want to marry this man, and she has another love.” And he ordered the father to let her marry who she wanted. I thought it was a nice story that showed how much story you can pull from a rug. I was trying to really capture that in this work as well.

WW: Sagging from an emotional weight.

RM: Yeah, there’s an emotional weight to it and importance, the significance, the sadness.

Aluminum Rug detail

Photo credit: Roda Medhat

WW: One other thing I wanted to bring up is the series Aluminum Rugs, which I’m seeing a lot around the studio.

RM: They’re aluminum rugs with the water jet cut pattern, and then I put a vinyl over them and I heat formed the vinyl. That’s how you get the colours out of them. After I created those works,I was like, they’re too flat. That’s where these LED ones came from. Originally, I wanted to create another version of FARSH 2, but I started painting and I was like, it’s too hard to paint successfully so I transitioned to vinyl.

It was about exploring other places I can place my work because a lot of these works are impermanent. How can I create work that has a longer life, is more easily placed in different places, can advance a career? So it progressed from those kinds of designs to the LED ones.

WW: It’s interesting to contrast the use of colour in the LED and the aluminum rugs. The aluminum pieces, a lot of them are very subtle in the colour differences. Do you feel like the high-contrast multicolour of the LED is something that you’re more drawn to?

RM: Not necessarily. I love the way that the aluminum looks, and I would produce more works like this. I think what I’m more drawn to is the form of the three-dimensional. So if I could translate this into a more three-dimensional form, I probably would. Actually, I didn’t even think about it until now, but maybe that’s the next thing I’ll do.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

About the Artist

Roda Medhat

Roda Medhat is a Kurdish born artist, currently based in Toronto, Canada. He obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from OCAD University. Additionally, he studied film production at FAMU Film and Television School of Prague. Roda is completing his MFA at the University of Guelph. Roda’s work has been recognized by the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts. In 2023 Roda was selected as the 401 Richmond Career Launcher Prize recipient. In 2024 he was awarded a place in the CIBC C2 Art Program. His creative vision often centres on the experience of being a child of the 1.5 generation, exploring the complexities of living between cultures, particularly as a Kurdish artist. Through his art, Roda seeks to bridge cultural divides and promote a sense of shared human experience. His dedication to creating socially impactful and visually stunning art underscores his commitment to advancing the boundaries of contemporary art.

About the Writer

Wenying Wu (she/her) is a student of English and Chinese literature beginning her MA in Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto in September of 2024. Her research interests include science fiction, body horror, and the representation of dreams. Wenying was the Cultural Content Writer at STEPS during the 2024 summer season.

Have a story to pitch or an exciting idea on how we can work together on a Fieldnotes feature? Contact us to get the conversation started.