Beyond a greenwashed canvas: Creative placemaking and public art strategies for environmental resilience

A solar-powered sculpture made from recycled materials in Chinguacousy Park (Brampton, Ontario) as part of the 2024 RECLAIM Public Art Residency with STEPS and the City of Brampton

Artist Credit: Sar Wagman

Photo Credit: Herman Custodio

This feature is part of Fieldnotes, a public art blog series by STEPS that promotes inclusive and innovative public art through interviews, storytelling, case studies, and knowledge sharing.

In the midst of an environmental crisis, public art needs a sustainable reboot. As the needs of the public respond to climate change, public art should shift to reflect climate justice and other environmentalist principles. However, while eco-friendly messages abound in art, sustainable practices are less common. Many default modes of artistic production are interwoven with unsustainable models of consumption, ignoring the finite nature of our planet’s resources. If public art is to promote environmentalist messaging, then it should also practice what it preaches, modeling sustainable creativity for an eco-friendly future.

But sustainable artistic practice is easier said than done. On one hand, public art tends to avoid some of the environmental pitfalls of other forms of art. One major sustainability concern for the art world is the carbon footprint of museums and galleries. Since public art exists in public spaces—either outdoors or in buildings already serving some other public function—the maintenance of dedicated artistic space is not a part of its environmental impact. That being said, public art not only inhabits public spaces but also creates and defines them. As cities across the world go green, art has the potential to model sustainability for the public and transform our shared spaces into something more eco-friendly.

One complicating factor in our pursuit of sustainable cities is the material cost of revitalization. If the “old” order is what brought us to today’s climate crisis, then the impulse to make it new, make it sustainable, is completely reasonable. From extreme weather events to decreasing biodiversity, the world inaugurated by climate change is a new one, and that newness demands a unique artistic language that takes into account the devastating consequences of human impact on the environment.

But even sustainable reinvention cannot be conjured out of nothing. The desire to create new artistic monuments or community spaces that appear eco-friendly risks becoming superficial greenwashing, hiding the unsustainable reality under the appearance of environmentalism. From building green space to installing ecocritical public art, it’s straightforward to make a seemingly greener world, but what carries the cost of this renewal? Will these eco-friendly interventions have the longevity or reusability to justify their manufacturing costs? In recent years, living walls of plants adorning urban buildings have become popular signals of eco-friendly architecture. However, their green appearances belie the potential ecological costs; when improperly designed, living walls face issues of maintenance, irrigation, and short lifespans.

Creative placemaking with sustainable intentions can fall into the trap of overconsumption, wastefully using resources and producing emissions in the pursuit of creating something new. To foster materially sustainable approaches to activating public spaces, public art needs to shift away from a fetishism of the new to a cultivation of the present. It is not enough to speak a sustainable message, to take on a green aesthetic. Public art must do the harder, dirtier work of building sustainable spaces and artistic economies.

Green Placemaking: The Ecology of Sustainable Public Spaces

While urban plant life appeals to our expectations of an eco-friendly aesthetic, the design of truly sustainable green public spaces must consider both the space’s relationship to the local ecosystem and the environmental impact of manufacturing. Green spaces can provide a wide range of environmental benefits, from reducing urban heat islands to improving air quality, but not all green spaces justify their cost. Many public green spaces still maintain traditional turfgrass lawns, despite well-documented environmental drawbacks of low biodiversity and high water consumption. Green spaces can serve as carbon sinks, but that effect is defeated if outweighed by the carbon footprint of construction and maintenance.

Painted planters draw attention to urban greenery in Clarkson Village BIA (Mississauga, Ontario)

Artist Credit: Marie-Judith Jean-Louis

Photo Credit: Selina McCallum

Key to sustainable placemaking is an active dialogue with the biodiversity and ecology of the land itself, taking into account both the pre-existing ecosystem and regional issues of environmental injustice. In these conversations, the voices of local Indigenous artists and stakeholders are crucial—with respect to both Indigenous sovereignty and ecological knowledge.

Created under the direction of T’uy’t’tanat Cease Wyss, a Skwxwú7mesh, Sto:Lo, Hawaiian, and Swiss artist and ethnobotanist, x̱aw̓s shew̓áy̓ New Growth《新生林》 is a vacant-lot-turned-garden in Vancouver’s Chinatown, which is located on the unceded territories of the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations. Transforming vacant space into a hub of community and biodiversity, the garden reintroduces Indigenous plant species into Chinatown “to map the future ecosystem we want to live in.” There is no one-size-fits-all solution to sustainable green spaces, and x̱aw̓s shew̓áy̓ New Growth《新生林》offers an inspiring example of a garden tailored specifically to local community and ecological needs.

Thoughtful design is only one hurdle to making a sustainable green space. For production to be worth the environmental cost of labour and materials, planners must invest into the longevity of the project. According to a 2024 study comparing the carbon footprint of urban and commercial agriculture, non-residential urban gardens are on average six times more polluting than commercial agriculture. However, the research does not condemn all community farms; instead, it suggests that more sustainable practices, such as long-term maintenance of established agricultural sites and circular reuse of waste products, can allow urban farms to contribute to environmentally-friendly food systems.

For projects that don’t have the longevity of community gardens, the relationship to local ecology is still a key consideration. Traditional public art might not be able to serve as a carbon sink, but it can potentially damage its environment. Historically, vivid but toxic paints have been produced from materials like lead and arsenic.

Today, poison and pigment no longer go hand in hand, but many artistic materials still have insidious effects on the environment. Both natural and plastic-based paints can leach particles into runoff, having a similar effect as microplastics on the marine environment. Public art especially must consider the polluting potential of the artistic materials, since the daily wear and tear experienced by outdoor art installations means that fragments of debris from the works will inevitably make their way into the surrounding water and soil.

Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose: Circulating Artistic Resources

Not all public art materials have an eco-friendly afterlife, and not all of them have eco-friendly origins either. Is it possible to opt out of unsustainable resource extraction, even in a limited artistic scope? We cannot always buy our way into sustainable consumption; much of the carbon footprint of artistic materials comes from the moment of production, not their disposal.

Around the world, unrecycled bottles and other plastic waste accumulate

Photo Credit: PxHere

Recycling promises a diversion of waste, but the reality of waste treatment is that very little of our plastic waste actually ends up recycled. As much as 91% of plastic in Canada ends up in the landfill, either directly through the trash can or dumped from recycling facilities. Part of the problem is that recycling plastic is actually quite difficult. While one type of paper is usually quite similar to another, plastic is more of a blanket descriptor rather than a unified, interchangeable material.

To accommodate the resource limitations of our planet, the Gallery Climate Coalition (GCC) advises creating a circular economy for the art world, which subverts the default linear economic model that assumes the disposability of resources. To implement a circular economy, the GCC emphasizes reuse, repair, and sharing of material resources before disposal. Of course, many of the tools and supplies of public art can be quite specialized and thus not necessary beyond one or two uses. Therein lies the importance of sharing; to take full advantage of the life cycles of our planet’s finite resources, we must connect to our communities and allow resources to move to where they are most needed.

Amid the growing push for sustainability in the arts sector, artists can take advantage of a variety of resource sharing initiatives, including several creative reuse depots across Canada. These include University-affiliated waste diversion programs, such as Concordia University’s Centre for Creative Reuse (CUCCR) in Montreal or the Ontario College of Art & Design (OCAD) University’s ReUse Depot in Toronto. The CUCCR and the ReUse Depot divert useful artistic resources from the waste of their respective institutions while also serving as a free and sustainable source of artistic materials. Also in Ontario is the Artist Material Fund (AMF), a material redistribution project founded by curator Suzanne Carte. AMF, which has operated several pop-up reuse depots, salvages waste from cultural institutions across the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area.

Creative reuse projects can also function as affordable second-hand shops, bringing the thrift store experience to the arts sector. In British Columbia, the non-profit SUPPLY Victoria operates the Creative Reuse Centre, a low-cost store for second-hand art supplies. With a similar model, ArtsJunktion is a charitable organization in Winnipeg that sells reusable artistic materials on a pay-what-you-can basis, as well as organizing art workshops open to the community.

One Artist’s Trash: Cycles of Production in Public Art

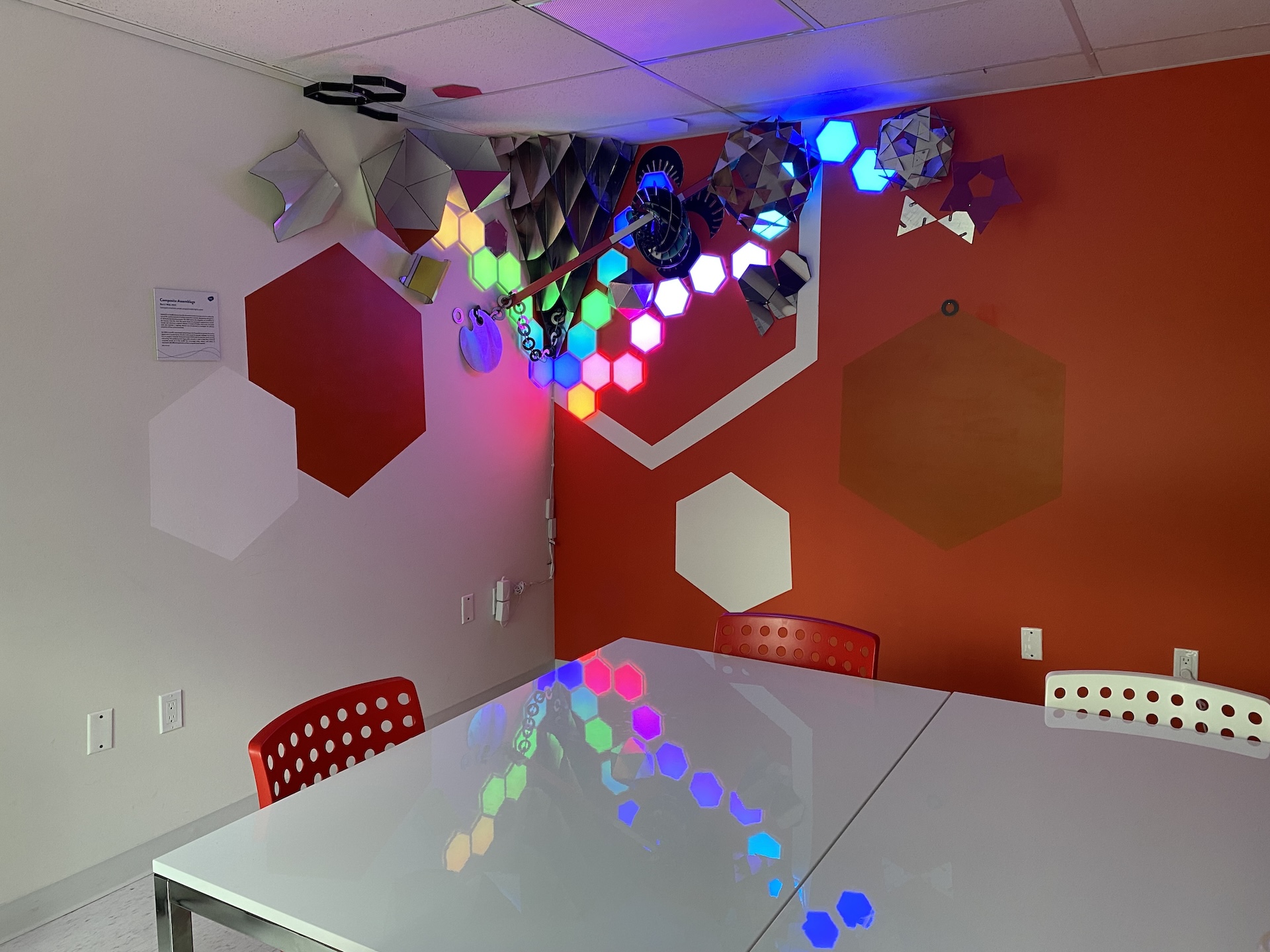

Shifting multi-coloured lights play off the reflective surfaces of upcycled AluPanel

Artist Credit: Ron Wild

Photo Credit: Raquel Paredes

What is the life cycle of public art? While artistic resources can be recirculated into the artistic ecosystem, the byproducts of public art can require some more creativity to upcycle. Ron Wild’s Composite Assemblage is a dazzling 3D sculpture built from a curious material: AluPanel from construction site hoarding artwork. In the context of construction, hoarding refers to temporary walls erected as barriers between a construction site and the street, for both aesthetic and safety purposes.

As a social enterprise, STEPS offers the service of facilitating PATCH (Public Art on Construction Hoarding) Exhibits—vibrant artwork to animate construction sites. In cities such as Toronto where municipal bylaws require public art at construction sites, upcycling can give these temporary artworks another use. Composite Assemblage, which decorates the STEPS Downtown Toronto office at Art Hub 27, draws out the second-life creative potential of AluPanel and explores its reflective properties through a lighting element.

Composite Assemblage by Ron Wild

Photo Credit: Ayesha Khan

While sustainable life cycles for public art challenge the use of traditional artistic materials, they can also be a source of creative synergy. In partnership with the Victoria Arts Council, STEPS facilitated the RECLAIM Public Art Residency in 2023 to provide participant artists with the environmental and artistic mentorship necessary to implement sustainable practices in their own art. Led by Vancouver-based artist Germaine Koh, RECLAIM provided artists with the capacity to engage in sustainable artistic production and to unearth the complex underlying systems that circulate our material culture.

For participant artist Carollyne Yardley, the residency was an opportunity to explore environmental ethics through public art. The artist, who created the sculpture series Speculative Futures for RECLAIM, uses art to explore “how we can engage the complexity of the climate emergency without omitting its scale or succumbing to eco-anxiety.”

Accessible public art, the artist explains, “[can] encourage the public to observe their surrounding ecologies […] while reducing the production of new materials and thinking about the unique hybrid ecologies in an urban environment.” Through Speculative Futures, Carollyne Yardley explores the fascinating potential of future geologies, speculating on “new taxonomies of rock records birthed from the contamination of plastic, construction waste, stone fragments, and organic remnants.”

Three sculptures from the Speculative Futures series, fabricated from recycled foam and objects, string, screen printing paint

Artist and Photo Credit: Carollyne Yardley

Although it offers accessibility and public reach for environmentalist messaging, public art also presents its own set of challenges to sustainability. “The world of permanent public art commissions is quite resistant to sustainable and low-resource approaches,” says RECLAIM mentor Germaine Koh. This attitude is informed by the perceived risk and unpredictability of unconventional production processes. Despite this resistance to sustainability and novel production processes, Germaine proposes a positive direction of change in the public art world, hoping to see more temporary opportunities—“which sometimes have lower requirements for over-engineered materials and a smaller environmental footprint.”

Despite these challenges in the realm of public art, a sustainable artistic methodology can also be a source of direction. “Limitations are a great prompt for creative practice,” Germaine Koh explains. “There’s nothing as scary as a blank canvas, but working with existing materials is rich in possibilities.” Indeed, sustainable artistic thinking can inspire us to reimagine what exactly counts as public art, thinking outside the box of our desire for novelty and overproduction.

Apart from making more new things, what can public art do for communities? Germaine is currently exploring one possibility through a rural art residency focused on “land-based, sustainable and community practices.” The residency prioritizes practice over product, so “new production takes a back seat to all of the other concerns that make for a sustainable artistic practice, like eating, wellness, and connection.”

Visitors explore an exhibition of sustainable artwork by the artists of the 2023 RECLAIM Public Art Residency

Photo Credit: Victoria Arts Council

Sustainability in public art is a challenging venture, one that must be fostered through a robust community of material circulation and knowledge exchange. There is no single, uniform solution for an eco-friendly public art practice, and our knowledge of sustainable practice is constantly evolving. By engaging in conversations about green placemaking and nurturing artist capacity for sustainable work, artists and institutions can pursue sustainability that goes deeper than a green appearance.

Further Reading

A (Public) Art Notice by the Synthetic Collective, Centre for Sustainable Curating, the Institute for Public Art and Sustainability (IPAS) at Evergreen Brick Works, and The Bentway

About the Writer

Wenying Wu (she/her) is a student of English and Chinese literature beginning her MA in Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto in September of 2024. Her research interests include science fiction, body horror, and the representation of dreams. Wenying was the Cultural Content Writer at STEPS during the 2024 summer season.

Interested in bringing sustainable public art to your community? Contact us to get the conversation started.