Announcing the new STEPS Public Art Blog Series!

STEPS Blog takes an in-depth look at the trends and tactics emerging in the field of public art, as our cities adapt to pandemic measures, changing patterns of use, and growing populations. The upcoming article series explores the Canadian public art scene, with a focus on new and innovative community-led programming, placemaking, and art interventions that are changing public spaces across the country.

To launch STEPS Blog, Cultural Content Writer Eva Morrison covers the CreateSpace Public Art Forum, drawing parallels between the ten artist talks on this year’s panel.

Read the full article on the CreateSpace Forum below! Stay tuned for more blog posts highlighting key concepts in public art, emerging artists to watch, and exciting new public art projects from STEPS and beyond.

Artist credit: Abject Who? by CreateSpace Public Art Forum participant Kawama Kasutu

The 2022 CreateSpace Public Art Forum

A Free Online Series of Artist Talks Explores Critical Frameworks and Contemplates Futures for Public Art in Canada

In January, the CreateSpace Public Art Forum launched with a panel of ten artist talks that approached different facets of placemaking in public art and identified a range of considerations, overarching issues, and emerging strategies in the field.

What does it mean to create space?

The CreateSpace Forum opened with a keynote address from artist Lori Blondeau and presentations from the panel of artists and cultural workers: Ammar Mahimwalla, Latifa Pelletier-Ahmed, Florence Yee, Jenel Shaw, Sanaa Humayun, Kiona Callihoo Ligtvoet, Dee Barsy, Excel Garay, Aubyn O’Grady, Su Ying Strang, and Amanda Lederle. The forum invites 45 participants, who identify as Black, Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis), racialized, rural and/or youth with disabilities and between the ages of 18-25, to respond creatively to these talks, producing artworks with support and feedback from peers and panelists.

The panel speakers discuss placemaking practices, city planning, and artistic development in urban and rural spaces, considering relevant issues like ecological injustice, ableism, limited diversity in positions of power, and epistemic violence. From a range of perspectives and approaches, the series envisions a future for public art that involves community engagement, acknowledges and works to eliminate systemic barriers in the field, and represents a multitude of identities and histories in common spaces.

Building community

One re-emerging theme across the series of artist talks was the importance of community in relation to public art-making. The panelists touched on the idea of community in different ways: exploring the benefits of building strong communities for BIPOC artists to navigate the predominantly white art world; considering the interrelationships at play when making artwork for a specific space; investigating how activism can empower change for different communities, and identifying the reciprocity between ecology and geographic communities.

Amanda Lederle raises important questions about the role of community members in placemaking projects, emphasizing hands-on processes that move away from traditions of viewing the public as a detached audience or consumer. In their talk “Placemaking as a Tool”, Lederle says, “by nature, public art involves people…but in the making and sharing of the work I have some further questions: who is included in the making of this piece?” This approach considers everyone involved in a public art development by consciously recognizing who is consulted, who participates in the realization of the work, and who is invited to engage with the piece.

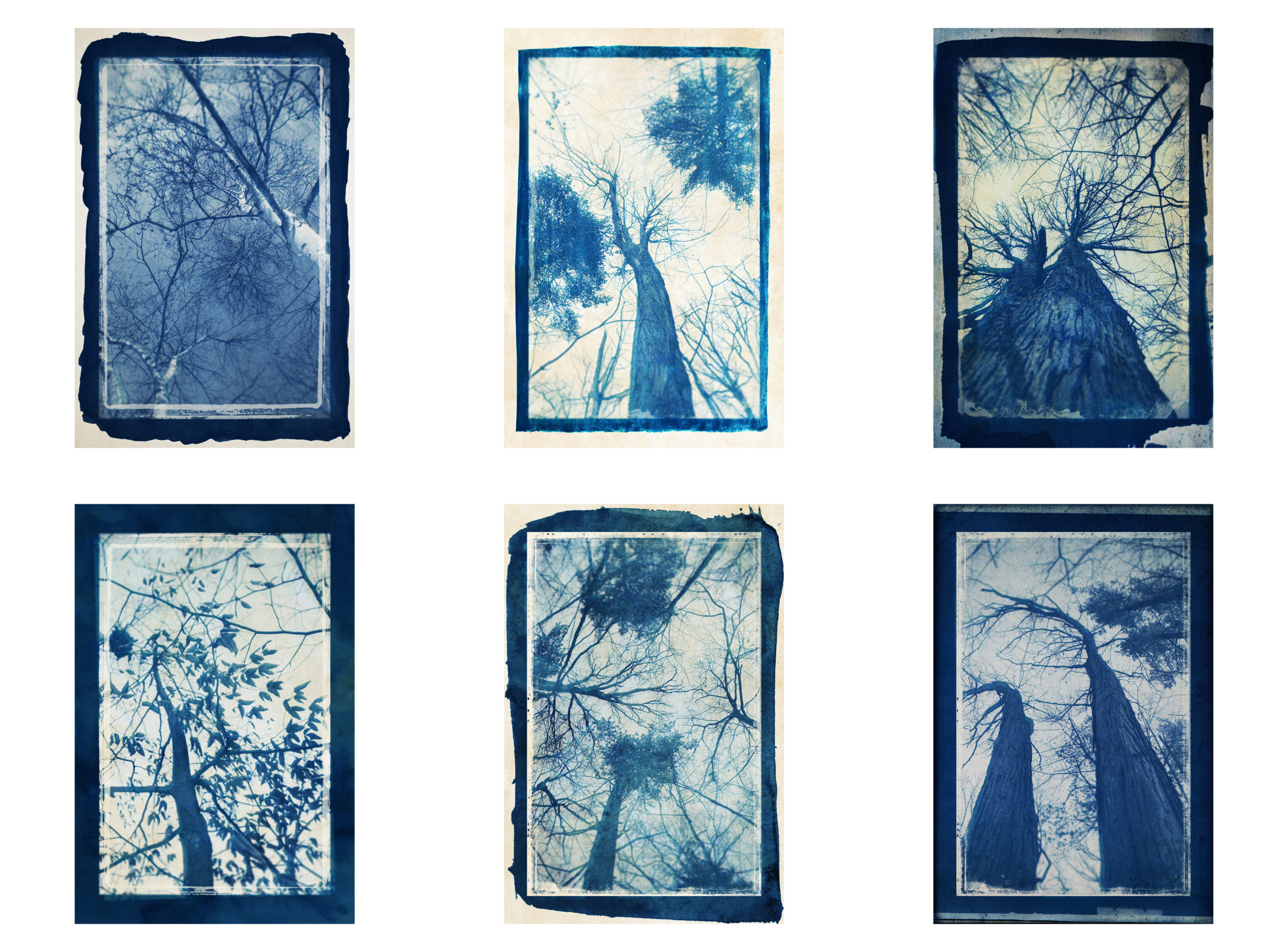

Artist credit: Trees Along the Trail by CreateSpace Public Art Forum participant Soka Lazara in response to talks by Dee Barsy, Amanda Lederle, and Latifa Pelletier-Ahmed

In her artist talk on visualizing interrelationships, Dee Barsy also outlines the importance of envisioning the potential for community engagement and impact when coming up with an artwork. She shares methods of visualizing potential projects with prompts like “who, what, where, when, why” that generate valuable questions like: “What is the history of the community? What is the history of the neighborhood or the land that this project will be taking place on? What will it bring to the community?”

This idea of community impact emerges in Florence Yee’s discussion on activist inclinations in public art, which can sometimes mean prioritizing community resources over the “creative” element of public arts. In their artist talk, Yee brings up the project Meditations In Concrete II by Phat Le and Benjamin de Boer, which redistributed their art budget to five grassroots organizations in order to implement their strategies to intervene against the hostile architecture in public spaces in Toronto. Yee explains, “this is an example of when public art shouldn’t be a creative project because it would worsen the situation of inequality and instead seeing it as an opportunity to enact wealth and resource redistribution.”

Latifah Pelletier-Ahmed stresses the value of communal knowledge and participation when approaching ecology in public art; not only do these ecosystems affect community members, but engaging with them requires collaboration because of the complexities involved. She explains “[there’s] folks who enter from a research/science point of view who spend lifetimes studying that, there’s people who carry traditional knowledge, Indigenous folks who have been building relationships with these beings for thousands of years and carry that legacy forward…so we can’t pretend as one individual to have enough information to really know all the ways to interact well and respectful with an ecosystem.” Again, collaboration is key to sustainable public art, over the idea of the individual artistic genius.

Community engagement can also mean actively building strong resource-sharing communities like Making Space, a virtual peer mentorship collective created for and by BIPOC artists and creatives. In their talk “On Making Space: Virtual Community Spaces”, speakers Kiona Callihoo Ligtvoet and Sanaa Humayun shared their journey founding the collective, which exists outside the traditional operational systems of galleries and artist-run-centers, aiming to create a non-hierarchical space for peer-mentorship, workshops, and skill-sharing, and promote opportunities for equity-seeking groups. As Humayun explains: “I never understood what community meant until we created Making Space because I think we work in ways that are really in opposition to the rigid hierarchies of institutions and the gatekeeping of knowledge…We deserve a space with fewer barriers and more autonomy, that’s built around our collective joy and wants.”

Artist credit: Cracked by CreateSpace Public Art Forum participant Gladys Lou

Considering points of access

Acknowledging these barriers in the field of public art involves recognizing systems of inequality that are inherent to public spaces, both physically and in more intangible ways. The panelists highlighted the importance of accessibility in different facets, from application processes, to physical exhibition spaces, to systems of knowledge.

In her artist talk “Opening Up Public Art”, Su Ying Strang outlines some exciting changes as well as some ongoing challenges and systemic barriers in the field of public art. She points out recent growth in scales of opportunity, efforts to diversify juries deciding on public art projects, and an influx of mentorships, training opportunities, and workshops that contribute to an “opening up of different types of practices, of different types of opportunities [which] allows for a greater diversity of people to participate.”

However, as she explains; “there’s still a lot of barriers in place and there’s been limited diversity for the folks in positions of power for a very, very long time, and that kind of engrained barrier is really hard to work through…and as much as many institutions are doing that work now, it does take time, and it does take some pressure as well.”

This pressure takes different forms; there are public art projects with activist inclinations that emerge from community needs, like those outlined by Florence Yee, as well as types of artistic interventions that spark dialogue about societal issues. In the artist talk “Access As a Creative Catalyst”, Jenel Shaw describes her artistic intervention project that aimed to raise awareness around the physical barriers that exist in public space, by highlighting the lack of accessible entrances to art spaces in Winnipeg. This tactic promotes urban development that has accessibility in mind on a large scale; as Shaw asserts, “when you talk about disability, it’s not about individual access, but about access as a culture.”

Not all barriers are visible in space; in their artist talk titled “Knowledge Serves the Producers”, Excel Garay discusses epistemic violence, which they define as “the study of how violence is enacted through knowledge [that] critically asks: where does knowledge come from, and who is it for?” Referring to the work of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Garay points to the ways that politics, medicine, science, law, and economics systemically prioritize their producers, from majority Western frameworks. The talk explores the importance of expressions that disrupt the hegemonic knowledge systems in place that prioritize perspectives from a certain class, race, and identity.

Artist credit: Cultivation by CreateSpace Public Art Forum participant Kyla Lin James

Holding space for layers of meaning and identities

From a diversity of perspectives, the forum panelists advocated for public art to represent a multitude of identities and embrace differences.

Florence Yee references Getsy’s idea of “compulsory sameness”, in relation to public art that emphasizes a unified, apolitical civic identity. Yee discusses how activist projects can reject this, stating that: “public art engages in the troubles of placemaking by rethinking, crossing, complicating borders, queering identity formation, anti-classification and excavating multiple narratives of a place.”

From a different perspective, based in urban planning and project management, Ammar Mahimwalla addresses the multitude of narratives at play in public space in his talk “Exploring Public Spaces in Victoria”, defining public art as “a medium for layering narratives, memories, and identities of underrepresented and marginalized groups, especially Indigenous, Black, and people of colour communities.” Mahimwalla leads a walk through Victoria Street, where the city is aiming to develop infrastructure in consultation with members of the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations communities to change the narrative of the streetscape and try to make these communities feel welcome.

Artist credit: Firewalk by CreateSpace Public Art Forum participant Maneesa Veera

Aubyn O’Grady is also wary of unified identities in public space; she explains that the public art in Dawson City, Yukon represents a limited place identity that focused on the gold rush and mining activities. In her talk, titled “A Tailing Pile Can Be an Amphitheater”, she explores ways that public art can creatively and collaboratively reuse rural spaces and represent divergent identities and alternative histories there. As she asserts, “space that is considered public is complicated and often entangled in many, many, many layers of stories and understandings…in part, our job as artists is to show where those stories intersect to make that strata visible and to make sure to take our own location in that space into account as well.”

Because the concepts, methods, and mediums that build public art are evolving so rapidly, critical frameworks are still developing in the field. It’s an exciting time to challenge traditional ideas and exclusionary systems, ask questions, and develop public art practices that can benefit their community, work to break down barriers, and represent a plurality of identities and narratives.

All ten talks, keynote address, and virtual gallery of the artwork responses created by program participants are available in full on the CreateSpace Public Art Forum and the STEPS Youtube Channel.

The CreateSpace Public Art Forum is one of STEPS’ artist capacity building programs that supports artistic growth and represents a range of perspectives through public art programming. To learn more about STEPS’ residencies, workshops, and other future opportunities, you can subscribe to our newsletter.

About the Writer

This article was written by Eva Morrison (she/her), a writer, curator, and painter based in Montreal. Her work has recently been published by Culture Days, Winnipeg Arts, and FARR Montreal. She received a BFA from Concordia University in 2019, specializing in Art History and Studio Arts.

Supporters

CreateSpace Public Art Forum is supported by Canadian Heritage, Canada Council for the Arts, and CIBC